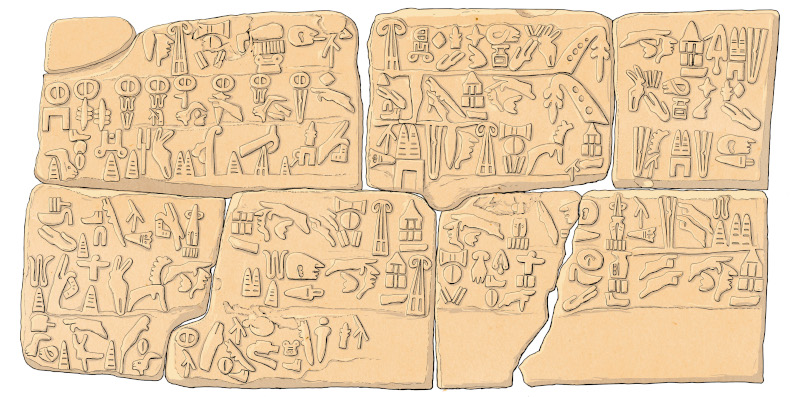

Luwian hieroglyphic inscription (4 m wide) from reign of King Šuppiluliuma indicating that the Lukka in southwest Anatolia were causing trouble (after J. David Hawkins 1995).

Myrina’s Journey to Atlantis © Nicholas Costa 2024

Diodorus Siculus’ Library of History is a mine of information about the ancient world, its peoples, histories, legends, and myths. Within its pages are to be found reports that are to be found in no other extant work of the classical era.

Most interesting in the current context is the remarkable story he narrates in Book 3. 52. At first sight it is so fantastical and has seemingly no bearing on anything narrated elsewhere about the Amazons from other extant sources, that hitherto the response has been to discard it totally as being a mere fabrication by a late mythographer with no bearing whatsoever upon reality.

However a closer analysis shows it to be something very different. Diodorus who lived c80-20 BC drew his story from the works of an earlier writer called Dionysus Skytobrachion, variously identified as Dionysus of Mytilene or Miletus. It is thought he was nicknamed ‘skytobrachion’ (literally, of the leathern arm) because of his prolific output. Unfortunately, except for the excerpts in Diodorus, none of his works have survived. (The full text of Diodorus’ narrative concerning Myrina can be found at the end of this article.)

The Key elements of the story

So much information is contained within this story that in order to understand it better it is best to break it down into its constituent parts with an emphasis upon the clues given as to its geographical location:

1. It was set in the western parts of ‘Libya’, on the bounds of the inhabited world.

2. On an island called Hespera (meaning in the west), set in a marsh called Tritonis.

3. The marsh was near the ocean which surrounds the earth and named after a river Triton which fed it.

4. The marsh was near Ethiopia and “that mountain by the shore of the ocean which is called by the Greeks Atlas”.

5. The island was of great size.

6. The Amazons subdued all cities on the island except one: Mene

7. Mene was considered sacred and inhabited by Ethiopian Ichthyophagi (fish eaters).

8. The island/city was subjected to great eruptions of fire. It possessed a multitude of precious stones.

9. The Amazons subdued many of the neighbouring tribes of Libyans and nomads.

10. They founded a great city in the marsh Tritonis called Cherronesus after its shape.

11. Setting out from city of Cherronesus, the first people against whom they advanced were the Atlantians.

12. The Atlantians were the most civilised people. They were prosperous and they possessed great cities; the birth of the gods was placed in these regions that lie along the shore of the ocean.

13. The Amazons favoured cavalry to an unusual degree. They used swords, lances, and bows and arrows with which they could shoot backwards when retreating.

14. On entering the land of Atlantians they defeated the inhabitants of Cerne and razed the city to the ground.

15. Myrina founded a city that bore her name in place of the razed city and settled both captives and natives who so desired to settle there.

16. The Atlantians were often warred on by the Gorgons, a folk who resided on their borders.

17. ‘Amazon Mounds’ (3) were raised in memory of fallen in battle against Gorgons.

18. The Gorgons were later subdued by Perseus.

19. The Amazons and Gorgons were entirely destroyed by Heracles when he visited the regions of the West and set up his pillars in ‘Libya’.

20. The marsh Tritonis disappeared from sight in the course of an earthquake, when those parts of it, which lay towards the ocean, were torn asunder.

The Far West

As can be readily seen, there are an incredible number of clues as to the location of the Amazons. The first thing it is necessary to do, however, is to discard all notion that the location is set in the far west on the coast of North Africa, facing the Atlantic Ocean. The seeming contradiction in the text of Ethiopia being next to Libya should itself determine that the text is referring to an entirely different location than the one currently conjured.

Even though Pliny (AD 23/24 – AD 79) informs us, based upon a report of Polybius, (Book 6.36.):

“That (the island of) Cerne lies at the extremity of Mauritania, over against Mount Atlas, a mile from the coast… There is also reported to be another island off Mount Atlas, itself called Atlantis, from which a two days voyage along the coast reaches the desert district in the neighbourhood of the Western Ethiopians… Opposite the cape are also there reported to be some islands, the Gorgades, which were formerly the habitation of the Gorgons… These island were reached by the Carthaginian general Hanno, who reported that the women had hair all over their bodies, but that the men were swift of foot and got away; and he deposited the skins of two of the female natives in the Temple of Juno as proof of the truth of his story and as curiosities… Outside the Gorgades there are also said to be two Islands called the Hesperides.”

Anyone who believes this area to be the actual location of the Gorgons, Amazons and Atlantians is, like Hanno’s female natives, making a monkey of themselves. As even Pliny goes on to say:

“The whole of the geography of this neighbourhood is so uncertain.”

Certainly by Pliny’s time these areas did bear these names, but for very obvious reasons. The discoverers named them after the things or places they were familiar with; in much the same way as say Christopher Columbus named many of the islands in the Caribbean. Nobody now would dream of locating Spain in the Caribbean on the basis of his having called one of the islands there Hispaniola. Surely if the heroes of Greek mythology wanted to plunder, loot, rape, or pillage they had many opportunities far closer to home.

What this is in fact is a classic case of location displacement a thing which is very common in the Greek myths, aspects of which have been well explained by Peter James in the Sunken Kingdom.

The Three Continents named wrongly

Another very important clue is to be found in Strabo’s Geography (1.4.) where he writes:

“and the Greeks named the three continents wrongly, because they did not look out upon the whole inhabited world, but merely on their own country and that which lay in the direction opposite, namely Caria where Ionians and their immediate neighbours now live; but in time ever advancing still further and becoming acquainted with more countries, they have finally brought their division of the continents to what it now is. The question, then is whether the ‘first men’ who divided the three continents by boundaries were those ‘first men’ who sought to divide by boundaries their own country from that of the Carians, which lay opposite; or did the latter have a notion merely of Greece, and of Caria and a bit of territory contiguous thereto, without having in like manner a notion of Europe, Asia, or of Libya…”

Lybia-Luwia-Lydia

In addition, note, the similarity of the Greek name Libya (?????) and the Hittite name Luwia for the coastal region of Asia Minor known in Greek as Lydia (?????). Likewise note the similarity of the name Africa (??????) for the continent and Phrygia (??????) the region in Asia Minor, as well as the derivation of the word Asia (????) from the Hittite region of Assuwa.

As shall be demonstrated in confirmation of Strabo’s statement; the area the myth is actually referring to is to the south west coast of Asia Minor. Bearing this in mind, can one therefore pinpoint a location that answers to all the salient points in the myth?

Triton

It is first necessary to note that the names Triton and Tritonis are not of much help. Even though a Lake Tritonis was to be found in later years in North Africa and was to be identified with the lake Tritonis in the myth it was in fact (if you’ll excuse the pun) just a red herring. Triton appears to have been an early word denoting ‘river’, ‘water’, or ‘sea’. There was even a sea god called Triton, and the word can also be detected in the name of Poseidon’s wife: Amphitrite. Therefore what the name says is ‘lake or body of water’ However from the description it is possible to pinpoint the exact location.

“This marsh was near the ocean which surrounds the earth and received its name from a certain river Triton which emptied into it; and this marsh was also near Ethiopia and that mountain by the shore of the ocean which is the highest of these in the vicinity and impinges on the ocean and is called by the Greeks Atlas.“

Ethiopia

The word ‘Ethiopian’ used to describe the fish eaters should also not overly concern. Greek use of place names in early myth was to say the least very flexible, Ethiopia did not always refer to a place in Africa; it could be used to describe (as the name implies) somebody of a darker skin colour. The island of Lesbos (so Pliny informs us) was once also known as Aethiopis. Therefore somebody from Lesbos could have once been called ‘Ethiopian’. Notably Mytilene in Lesbos was said to have been named after Myrina’s sister so she could have been described as Ethiopian.

Likewise Aethopis is the title of a lost work by Arctinus of Miletus, with the first part known as the Amazonia. It was part of the Trojan War cycle. Its central image concerned Achilles’ killing of the Amazon Queen Penthesileia where in one version of the story he notably buries her in Lycia.

Merops who is frequently associated with the island of Cos is also depicted as a king of Aethiopia by Ovid in Metamorphoses (1.760 ff & 2.184).

An Ancient Joke

Note the literal meaning of the name Aethiopia in Greek: which is a compound of two Greek words aitho/ I burn and ops/ face- translating therefore as burnt-face. A very appropriate name given what happened in the vicinity of Cos in the early second millenium BC.

One therefore also needs to question as to where Memnon who was killed by Achilles in the Aethiopis actually came from, and it would appear given the current interpretation that he actually came from the region around Caria.

According to Herodotus there was a site known as the palace of Memnon on the old road between Smyrna to Sardis and he names Ephesus as Memnon’s city (Book 5:53-54). According to Quintus Smyrnaeus, Memnon said that he was raised by the Hesperides on the coast of Oceanus.

Island

Hesperia, or ‘western land’ is described as being an island. It could have been an island in the accepted sense of the word but equally the word ‘island’ was frequently used in ancient times to describe an area of land bounded by rivers or water. This is confirmed by Michael Wood in his book In Search of the Trojan War when he writes:

“Pausanias says that ‘some people think Enispe, Stratie and Ripe were once inhabited islands in the (river) Ladon’, to which he replies, ‘anyone who believes that should realise it is a nonsense: the Ladon could never make an island the size of a ferry boat!’ But if the word for island (nesos) is interpreted (as it can be) as a piece of land between a river and its tributary, then Dimitra could indeed be called an island in the Ladon, between the main river and its two tributaries.’”

In fact one only has to think of the Greek designation for the Peloponnese (island of Pelops) to realise just how flexible the term could be. By the same token the entire Turkish mainland, surrounded as it is on three sides by sea could be called an ‘island’.

Because the west coast of Asia Minor was the area in which it is known the Mycenaean Greeks to have been most active it makes sense in conformity with Strabo, to look in that area to see if one can locate:

1. A city or area known as Cherronesus.

2. A volcano and an area subjected to seismic activity, which led to subsidence of the land.

3. A marsh fed by a river.

4. A high mountain nearby ‘‘known as Atlas to the Greeks”.

5. A city of people noted for being eaters of fish.

6. Another city co-founded by ‘Amazons’ and ‘Atlantians’.

7. A group of people known as Atlantians. The birthplace of the Gods.

8. A group of people known as Gorgons.

1. The Cherronesus.

The legend says that the Amazons lived on an island called Hespera (western land). As noted the Greek designation of what constituted an ‘island’ was quite a loose one. It was essentially any area of land bounded by water, and as George Bean points out in Turkey beyond the Maeander the term was also used to denote a peninsula. In addition, the myth speaks of a city called Cherronesus, which quite literally means ‘hand island’. The word Cherronesus or Cherronessus was often used by the Greeks to describe as its name aptly describes a peninsula. The logical implication therefore is that it was located on a peninsula rather than an island or a city.

The coast of Caria between Rhodes and Samos has two notable peninsulas. According to Diodorus (Book 5, 60-63) the Cnidus peninsula opposite Rhodes was known as the Cherronesus. It is located directly south of the Myndus peninsula on which are located the ruins of Lelegian settlements. As demonstrated in Atlantis, the Amazons, and the Birth of Athene the Lelegians occupied the same regions as those purported to be occupied by Amazons Both these peninsulas, amongst other things, had some claims to fame in antiquity of a very singular nature which are detailed in the book including the Lelegian tombs. The major city of Halicarnassus (present day Bodrum) was situated here. It was where the famous mausoleum of Halicarnassus with its carved frieze of the Amazonomachy was located, mirroring the tombs of neighbouring Lycia. It was considered in antiquity as one of the Seven Wonders of the World. Notably it is in this region (Caria and Lycia) that the earliest legends locate the Amazons and not as popularly imagined on the river Thermodon.

2. Volcanic Island

At the opening of the sea between the Myndus peninsula and the Cnidus peninsula (the Cherrsonesus of Diodorus) are to be found the two islands of Cos and Nisyros. The island of Nisyros is in fact a volcano that has been the subject of a number of eruptions in historical times. Between Nisyros and Cos are the islets of Yiali and Strongyle, remnants of a huge eruption which occurred at some time in the past.

The classical authors record a number of things about this area. Strabo writes (10. 5. 16.):

“They say that Nisyros is a fragment of Cos, and they add the myth that Poseidon when he was pursuing one of the giants Polybotes, broke off a fragment of Cos with his trident and hurled it upon him, and the missile became an island Nisyros, with the giant lying beneath it. But some say he lies beneath Cos.’’

Poseidon was actually worshipped on Nisyros as ‘Nisyreus’. Pliny records something more explicit. In Book 5.36, he states that: “the island of Nisyros, formerly called Porphyris, is believed to have been severed from Cos.’’ Porphyrion is incidentally the name of another of the giants in the Battle of the Giants.

Diodorus (5.54.) records that:“The ancient inhabitants of Nisyros were destroyed by earthquakes, and at a later time the Coans settled the island.”

Poseidon (the sea) is represented as striking Cos with his trident. This is indicative of a large earthquake or eruption followed by a tidal wave. Whilst Polybotes conceived as being buried under both Cos and Nisyros, is a metaphor of the region’s volcanic arc.

In Nonnus (Dionysiaca I. 287) there appears to be an allusion to this event when he describes the monster Typhoeus. He writes:

“Typhoeus, holding a counterfeit of the deep-sea trident, with one earthshaking flip from his enormous hand broke off an island at the edge of the continent which is the kerb of the brine, circled it round and round, and hurled the whole thing like a ball.”

The effects of such an event were surely devastating and one can find no end of allusions and references to this in Greek mythology concerning the coastal regions of Asia Minor.

Diodorus writes (Book V. 82.):

“The mainland opposite the islands (i.e.Lesbos, Chios, Samos, Cos, and Rhodes), we find, had suffered great and terrible misfortunes, in those times because of the floods. Thus since the fruits were destroyed over a long period by reason of the deluge, there was a dearth of the necessities of life and a pestilence prevailed among the cities because of the corruption of the air.”

Tellingly, the main area of devastation is located on the coastal mainland, and not the islands, which would therefore argue strongly against identification with the eruption of Thera as being the central event for this particular catastrophe. The ramifications of this are explored in much greater detail in the book.

Birth of Hephaestus

In addition one could also cite the story of the birth of Hephaestus (quite literally ‘volcano’) who had been born from Hera’s thigh. If Hera’s head is seen as the island of Samos (the centre of Hera’s worship) then Cos/Nisyros to the south of this could be seen as representing her thigh. Significantly too Hephaestus is often depicted as lame in one leg which indicates an eruption. This is further underlined by the myth of Athene who in some accounts is depicted as the daughter of Hephaestus. In other accounts he is represented as trying to rape her unsuccessfully, but manages to ejaculate on her leg. This imagery of the ‘thigh’ is important in that it ties in, Hera, Hephaestus, and Athene, but also the god Dionysus (who is said to be reborn from the thigh of Zeus) and the Egyptian god Seth who was equated with Typhon, whose home is depicted as the constellation of the ‘Thigh’.

The story of the birth of Athene by the shores of Lake Tritonis also provides further clues as to location and timing.

Precious Stones

Note also at this point that the ‘island’ is said to have possessed a multitude of precious stones: “anthrax (dark redstone such as carbuncle, ruby, and garnet), sardion (cornelian, sardine), smaragdos” (any green stone). The presence of these stones is consistent with an area with volcanic connections. Samos for instance is noted for the presence of garnets. Garnets are to be found in all kinds of metamorphic rocks, in schists, marble and phyllites. Another type of metamorphic rock, the Serpentine is mostly green in colour but showing red mottling.

Birth of Athene

Modern geology knows of a stratovolcano erupting about 160,000 years ago between Cos and Nysiros but apparently virtually nothing as yet of the eruption in exactly the same location delineated by the Greek Myths as the Birth of Athene c1796/5 BC!! Having said that at least one analyst has uncovered signs signifying eruptive activity in the 2nd millennium BC. There now seems to be a creeping recognition that something more recent occurred in the region:

“a worst-case-scenario phreatomagmatic eruption at Nisyros would threaten not only the island’s inhabitants, but also those of Kos. The very young (probably prehistoric) age of the last explosive eruption of Yali also makes this centre a threat.” (Volcanism of the South Aegean Volcanic Arc, Georges E. Vougioukalakis et al. 2019)

3. The river Triton and the marsh Tritonis

The myth states that in the marsh Tritonis, on the island of Hesperia the Amazon city Cherronesus was located. The marsh was fed by a river called Triton. As noted the Cnidus (Datca) peninsula and the neighbouring Myndus peninsula are the heartland of the Lelegian/ Amazon mythos. In particular the river adjoining the Cnidus peninsula and flowing into the Aegean was known in antiquity as the Indus. It defined the border between Caria and Lycia. Ovid (Metamorphoses 9. 652 ff) refers to the Nymphae Lelegeides (Nymphs of the Leleges) who were represented as daughters of the (Indus) river.

Tellingly this produces a synthesis here between two seemingly divergent narratives, that of the original location of the Amazons and of Nonnus’ Dionysiaca who depicts the god Dionysus waging a protracted war against Indians.

By definition, it is unlikely that the marsh Tritonis in its original form is still in existence, since the myth says that it disappeared. Notably the area along the entire Carian coastline when it is fed by a river has been subjected to heavy silting. Marshlands abound in the region. George Bean writes:

“The great marsh, now largely reclaimed, at the mouth of the Saricay to the north-east of Gulluk was in antiquity sea; an inscription tells us that two citizens of Iasus persuaded Alexander the Great to restore to the city possession of the ‘Little Sea’, that is without doubt the area of the marsh.

Just slightly to the north, is the ancient peninsula on which Miletus was situated and the gulf to the north of this (the Latmian) was the outlet of the Maeander River one of the most important rivers in the region. The ancient gulf is now totally silted up, and the once coastal port of Miletus is now left high and dry some 8 km from the sea.”

4. Mount Atlas

So what is missing? Where was “that mountain by the shore of the ocean which is called by the Greeks Atlas”. One possibility is that the volcano on Nisyros was the original Mount Atlas, however as noted, there is a gulf now silted up, situated just to the north of the ancient city of Miletus which was called the Latmian gulf, it was so named after a city and a mountain which were to be found at its head.

George Bean writes in his book Aegean Turkey: “It is safe to say that no one who makes the excursion to Hercaleia will be disappointed. Though situated on the Ionian coast- for the lake of Bafa was in antiquity an arm of the sea- the city belongs, in character and history, to Caria. The scene is dominated by Mt. Latmus, whose serrated crest has given it the name of Bes Parmak, the Five Fingers. Some 4,500 feet in height, this wild and rocky mountain sends down a spur to the village of Kapikiri, and up this ridge run the walls of Heracleia, in beautiful masonry unusually well preserved. They rise, in fact, about 1,600 feet from the lake, but they climb into the sky, twisting and turning in a fantastic wilderness of rocks… The city was Carian from the beginning. In early times it bore the name of Latmus, distinguished only in gender from the mountain above… Latmus was always a holy mountain, and in the Middle Ages it was a favourite resort of anchorites and other holy men. Numerous monasteries and hermitages, which they founded, may still be seen; but in general they are high up among the wastes of rock, and are virtually inaccessible to the ordinary traveller.”

The name of the mountain is the surest clue as to its identification with the ‘‘mountain by the shore which is called by the Greeks Atlas.”

Greek mythology is replete with anagrams and doublets, and as can be readily seen, Lat(m)us is none other than the name Atlas in another guise. Is it coincidence that the city of Heraclea was located on this mountain for in mythology one finds the story of Heracles holding up the sky for Atlas?

The mountain of Endymion and Selene (Mene)

One other point to note is that the story of Endymion is located on this mountain. The best known stories tell of how he was loved by the moon Selene (already encountered her in the guise of Mene) – in one version he is meant to have discovered the secret of the phases of the moon. Endymion had had some sort of improper liaison with Hera causing Zeus to be upset, and as a consequence of which he had been granted a wish by Zeus it was said, to have anything he wanted. Endymion chose to sleep forever deathless and ageless. By Selene, even though asleep, he is meant to have become the father of 50 daughters. In classical times both Endymion’s tomb and sanctuary were to be found located on Mt Latmus.

The name Endymion is thought to derive from the Greek word ‘endyein’ meaning ‘to dive into’. This may in fact be another memory of the events surrounding the birth of Athene.

5. The Ichthyophagi, the Fish Eaters

Located on the coast in this region is the ancient city of Iasus. George Bean writes: “According to the Greek foundation legend Iasus was colonised by Peloponnesians from Argos. Their coming was not unopposed, and the local Carian inhabitants inflicted such losses on them that they were obliged to call in help from the son of Neleus, the founder of Miletus. As a result of this Milesian influx the city became Ionian instead of Dorian. The settlement by Argives is very likely to be historical; Homer gives to Argos the epithet Iason, and there was a small town of Iasus in the Peloponnese. The leader of the colonists was later supposed to be a man of the name Iasus, and he is represented with the title Founder, on Iasian coins; in this particular case there is perhaps slightly less reason than usual to regard him as mythical. The recent excavations have produced quantities of Minoan pottery in the buildings of the Middle Bronze Age levels.”

So what is special about Iasus? The myth explicitly refers to a city called Mene inhabited by Ethiopian fish eaters. If Iasus had any claim to fame in antiquity, it was for its fish! Strabo (Book14. 2.21.) writes:

‘‘then one comes to Iasus, which lies on an island close to the mainland. It has a harbour; and the people gain most of their livelihood from the sea, for the sea here is well supplied with fish, but the soil of the country is poor. Indeed people fabricate stories of this kind in relation to Iasus: When a citharoede (a cithara player who sang to its accompaniment) was giving a recital, the people listened for a time, but when the bell that announced the sale of fish rang, they all left him and went away to the fish market, except one man who was hard of hearing. The citharoede, therefore went up to him and said: “Sir, I am grateful to you for the honour you have done me and for your love of music, for all the others went away the moment they heard the sound of the bell.” And the man said, “What’s that you say? Has the bell already rung?” And when the citharoede said “Yes,” the man said, “Fare thee well,” and himself arose and went away.”

The quantities of Minoan pottery uncovered reveal that the city was in earlier times a Minoan settlement, and what more appropriate name for such a place than Mene, which could be a corrupt form of ‘Minoa’ a very common name in antiquity for Minoan settlements? As already noted the term Ethiopian could have readily been applied to the region in the vicinity of Cos. (Merops as noted was remembered as king of Cos and king of Aethiopia.)

One could ask how could there be such continuity. That a place should be noted for its fish, for something approximating the 1500-year time span between that of the mythical Amazons and Strabo’s time? A look in a contemporary travel guide will confirm something even more amazing. The Rough Guide to Turkey contains the following report: “Covering a headland almost completely surrounded by the Gulf of Asim, Iassos would seem, from a glance at the map, to promise great things. Alas the ruins, after the first few paces, fizzle to virtually nothing, and swimming in the sumpy coves nearby is hardly an inviting prospect. Only the excellent local fish, the best reason to visit, represent an unbroken tradition with the past. “

George Bean who writes of Iasus confirms this “Fish were abundant, as they still are; witness the big fishery at the head of the gulf… A gastronomer of the fourth century BC observes that the visitor to Iasus will find there prawns of great size but scarce in the market; and the present-day visitor to Gulluk will inevitably be offered fish for his dinner.”

The Sacred City

Mene is also described as a sacred city. It could have been so by reasons of political expediency in that it was controlled by a ‘regional super power’- the Minoan regime in Crete, or by virtue of the fact that it was dedicated to Mene. Mene was a title of Selene the ‘Moon’ goddess who was considered to be the sister of Helios the god of the Sun who also incidentally was the deity par excellence of the nearby powerful and influential island of Rhodes. Also, of great significance to this particular quest is the fact that the foundations of Lelegian buildings have been uncovered in Iasus.

Great eruptions of fire

The myth also says that they were subjected to “great eruptions of fire”. The tip of the Myndus peninsula is of volcanic origin as are central Cos and Nisyros which are in fact the heartland as noted of a still active volcanic complex.

The Nomad Tribes

The myth says that after they had subdued all the cities on the island except Mene, they: “subdued many of the neighbouring Libyans and nomad tribes” In Thucydides’ The Peloponnesian War, by way of an introduction he writes: “It appears, for example, that the country now called Hellas had no settled population in ancient times; instead there was a series of migrations, as the various tribes, being under the constant pressure of invaders who were stronger than they were, were always prepared to abandon their territory… Thus in the belief that the day-to-day necessities of life could be secured just as well in one place as in another, they showed no reluctance in moving from their homes, and therefore built no cities of any size or strength…”

The Leleges significantly are depicted as nomadic. In Book 1. 7. 3 Strabo says re Pisidia: “It is said that in ancient times certain Leleges, a wandering people, intermingled with them and on account of their similarity of character stayed there.”

A nomadic life therefore should not to be seen as the exclusive preserve of Arabian sand-dwellers.

6. Cerne

The myth states that: “The first people against whom they advanced, was the Atlantians, the most civilised men amongst those regions, who dwelt in a prosperous country and possessed great cities; it was amongst them we are told, that the mythology places the birth of the gods, in the regions that lie along the shore of the ocean… upon entering the land of the Atlantians they defeated in pitched battle the inhabitants of the city of Cerne, as it is called.”

Cerne was raised to the ground in its place Myrina: “founded a city to bear her name in place of the city which had been razed; and in it she settled both the captives and by any native who so desired.“

Given that in all probability Myrina is a deity metaphorically alluding to a natural calamity one should note that Nonnus (Dionysiaca 38.110-141) refers to Cerne (translated as Kerne) as the island upon which Helios and the nymph Clymene met and fell in love and got married. Their child was none other than Phaethon (an anagram of Typhon?) who crashed the sun’s chariot into the sea.

The Amazon myth is clear on one point, that there is a move out from Cherronessus and that the first people they encounter are the Atlantians of Cerne. Luckily, in the myth of Myrina, Diodorus goes on to say that: “it is related that the Atlantians, struck with terror, surrendered their cities on terms of capitulation” and that Myrina “bearing herself honourably towards the Atlantians, both established friendship with them and founded a city to bear her name in place of the city which had been razed; and in it she settled captives and any native who so desired.”

There is northward movement in the myth. Across the river Maeander lay Lydia. Lydia was the centre of a mighty empire in classical times -that of King Croesus. It was additionally considered to have had a culture of great antiquity, and said to have been the home of the Mother of the Gods, in conformity with the myth.

Ephesus

There are two likely candidates in the area. The most obvious city, because of its name, is Smyrna. The other less obvious one is Ephesus. Both cities have Amazon foundation legends, but in this particular instance Ephesus has the edge, particularly when one realises that its previous name was also Smyrna (Myrina preceded by the definite article), and that when Androclus the grandson of Codrus became king of the Ionians and sailed to Ephesus, so Pausanias informs us: “He expelled the Lydians and Lelegians from the upper city.”

Pausanias quoting Pindar says that the Amazons founded Ephesus on their way to fight Theseus in Attica. Who Theseus actually fought were the Carians mythologized as Amazons. The memory that is preserved in Strabo, is of a Carian invasion of Attica in the time of Cecrops a few hundred years earlier. He writes: “According to Philochorus, when the country (Attica) was being devastated from both the sea by the Carians, and from the land by the Boeotians, who were called Aionians, Cecrops first settled the multitude in twelve cities.”

Amazon Mounds

As noted earlier, Strabo’s comments concerning the remains of the Lelegians to be seen in his day in and around the territory of Miletus. Even in our day, one of the most distinctive remnants of the Lelegian culture is, to quote George Bean: “the remarkable ‘chamber tumuli‘ which are characteristic of the Lelegian country. They consist of a vaulted circular chamber approached by a passage and enclosed by a ring wall heaped over with loose stones.”

The Virgin Mary

At this point it would be appropriate to introduce yet another coincidence deriving from an entirely different source: the Greek Orthodox Church. For untold centuries, the Orthodox Greeks in the neighbourhood of Ephesus, and from a considerable distance beyond were in the habit of assembling at a small building just to the south of the city. Here they celebrated the Dormition of the Virgin Mary, whom they believed to have died there.

There are two traditions as to the Virgin Mary’s place of death. The canonical one holds that she died in Jerusalem at the age of 63. The rival tradition, dating from at least the council of Ephesus in 431 AD says that she came to Ephesus between 37 and 48 AD and lived and died there. At the site are the remnants of a house (now converted into a chapel) considered to be the home of the Virgin. The foundations of the house might possibly go back as far as the first century. It has long been a place of pilgrimage, with numerous cures and miracles ascribed to it.

To the orthodox world it is known as the Panaya Kapulu, or the house of the Virgin Mary otherwise known as Meryem Ana (Myri-Na?). Is this yet another fortuitous coincidence? Even though it is described as the house of Meryem Ana no tomb has not been found. The house is located on Coresus hill.

Pausanias tell us: “[7.2.6] the cult of Ephesian Artemis is far more ancient still than their (the Ionians) coming.[7.2.7] Pindar, however, it seems to me, did not learn everything about the goddess, for he says that this sanctuary was founded by the Amazons during their campaign against Athens and Theseus. It is a fact that the women from the Thermodon, as they knew the sanctuary from of old, sacrificed to the Ephesian goddess both on this occasion and when they had fled from Heracles; some of them earlier still, when they had fled from Dionysus, having come to the sanctuary as suppliants. However, it was not by the Amazons that the sanctuary was founded, but by Coresus, an aboriginal, and Ephesus, who is thought to have been a son of the river Cayster, and from Ephesus the city received its name.[7.2.8] The inhabitants of the land were partly Leleges, a branch of the Carians, but the greater number were Lydians. In addition there were others who dwelt around the sanctuary for the sake of its protection, and these included some women of the race of the Amazons.”

Note the similarity of the name Coresus and that of the city Cerne taken over by the Amazons.

Cavalry

The myth states that the Amazons favoured cavalry to an unusual degree. In his book entitled Lycian Turkey, George Bean writes (in connection with a place called Arsada situated high above the plain of the Xanthus valley):“A little above the village, beside the path from the north, on an outcrop about 8 feet high, is a relief representing a horse and rider. The horse is prancing to the right, the rider’s right hand is raised behind him and caries and elongated object of uncertain character, and he seems to have had a sword slung over his left shoulder. This looks like one of the Anatolian horseman-deities; the best known of these is Kakasbos, who appears frequently in western and northern Lycia.”

In addition, the main Greek myths involving horsemanship (Perseus and the birth of Pegasus, and Bellerophon the rider of Pegasus) have a marked connection with both Caria and Lycia. In classical times evidence exists in the form of sculptural monuments to the long-term specialist breeding of horses in the Carian region. A type of horse larger than that commonly encountered on Greek sculptural monuments is to be found depicted on carvings from Xanthus in Lycia and on the Mausoleum at Halicarnassos. (Cited by R.H.C.Davis: The Medieval Warhorse, 1989). Evidence can also be found in some of the early depictions of Gorgons which show them as having women’s heads, but horses’ bodies.

However it should be noted that even though many of the early references are to horses, it would appear that many of the animals of this early period in fact were either asses or were similar in size to asses.

“The horses of the early period were of a small type, like the modern Egyptian horse, resembling most closely the now extinct wild horse of the Ukraine, the tarpan, the variations from type being attributable to long domestication.” (Edward Bacon Archaeology Discoveries in the 1960s p155)

Note: by the time of Ramesses II, the Syrian warrior goddess Astarte had become the patron deity of horses in Egypt.

7. The Atlantians

Even though later Greek writers tended to place the figure of Atlas in the regions of the farthest west, a study of the actual mythology makes it patently clear that the figure of Atlas was a seminal one for the regions lying along the coast of western Asia Minor, particularly in the area which became known as Lydia in classical times.

On closer inspection even the name ‘Lydia’ can be seen to be a reversed version of Atlas (Aidyl =Atal). The association of the name with the region persisted even down to the time of the last king of Pergamon, Attalus III who bequeathed his kingdom to the Romans in 133 BC. It is in this context that one should consider the name adopted by a large number of Hittite rulers: Tudhaliya

Mount Tudhaliyas

The Hittite mountain god Tudhaliyas who gave his name to a succession of Hittite emperors may also be a reflection of the name Atlas. As with many rulers down the centuries they would often call themselves by names that were designed to show amongst other things how strong or terrifying they were. From at least the 15th century onwards Atlas-like figures are very popular motifs in Hittite art. In Anatolia in the Second Millennium, M. N. van Loon writes that the mountain Tudhaliyas was: ”privileged among mountain gods in being armed and free to move his feet.” This is confirmed by a ritual text in which the king repeatedly invokes him and four other mountains not to come and interfere: ”Mount Tudhaliyas, stay in thy place!”

Why should the Hittites be so concerned about a mountain moving? In addition why should a mountain be so important that a number of Hittite kings chose to name themselves after it? It is evidently a metaphor for a volcano.

One can detect the name Atlas in the naming of at least two mountains in the western region of Asia Minor: Tantalus (Sipylus), and Latmus in the south; as well as in the name of the goddess Leto, mother of Apollo and Artemis, who was ‘born’ on Cos.

8. The Gorgons

As noted earlier, the Lelegians can be equated with the Lycians. Another parallel can be struck with the Gorgons by equating them with the Carians. In Greek G (gamma) and K (kappa) were interchangeable depending on dialect. Both names have the common consonants GR/KR. The vowels between consonants were more fluid, thus Car and Cer and Cor were interchangeable. Thus Gorgons or more properly Gorgones can become Kar(k)ones or Cer(c)ones i.e. Carians. Significantly a number of the myths concerning the Amazons link them intimately both to the Gorgons and to a tribe known as the Gargarians, or Gargarentians. In proto history the Lelegians (Lycians) are intimately linked with the Carians, and explicitly in Strabo (Book 13), they are depicted as being near neighbours of a group known as the Gargarians. In the present exegesis Myrina’s Amazons, Lelegians, and Lycians were one and the same, likewise the Gorgons, Gargarians, and the Carians.

Carians

In the myth of Myrina, the Gorgons are depicted as fierce (female) warriors; the same applies to the image of the Carians in early history. The Carians were famous as mercenaries and for having invented 3 things: fitting crests on helmets, putting devices on shields, and making shields with handles. All these are implements of war. As already noted a number of the earliest representations of Gorgons extant in Greek art show them as having the head of a woman but the body of a horse. ( T.H. Carpenter Art and Myth in Ancient Greece p104.)

There are also geographical references in the ancient myths as to the actual location of the Gorgons. The most direct, that of Aeschylus, locates them near Kisthene, a city on the coast of Lycia. In the Cypria they were described as: ”fearful monsters who lived in Sarpedon, a rocky island in deepeddying Oceanus”.

As fearful monsters they evidently represent the Cos Nisros volcanic arc.

Remembering the Greek concept of an ‘island’, Sarpedon’s isle would be the area stretching from Miletus in Caria to the north, all the way to Lycia in the south. Ovid locates them in the inland parts of ‘Libya’ near the lake and the gardens of the Hesperides; this makes perfect sense if one bears in mind the current identification of the location of Lake Tritonis.

Another version of the myth has Perseus going all the way to Tartessus to slay the Gorgons. That’s a heck of a long way, for Tartessus was a kingdom located around the mouth of the River Baetis (Guadalquivir) in southwestern Spain!

Perhaps it was not as far away as it seems, when one bears in mind that the most influential traders or colonists of that particular region from the sixth century were people from Samos and Phocaea (in the north of Caria) who doubtless brought their legends with them. Both of these peoples take us back full circle to the coast of Asia Minor.

Summary

It should be clear from the above that either there are an amazing number of fortuitous coincidences in Diodorus’ seemingly vague and outrageous version of the myth of the ‘Libyan’ Amazons, or that (as is more likely) it was originally based upon a real historical record.

All the key geographical elements of the myth have been uncovered. This has given a real setting for a group of people known as the Amazons in myth and as the Leleges in proto-history, as well as identifying who the Atlantians and Gorgons were and where they were located. These identifications (as demonstrated in Atlantis, the Amazons, and the Birth of Athene ) have a momentous impact upon the interpretation of the ancient history of this period, and help explain many hitherto unanswered questions particularly the hitherto mysterious origins of the Hyksos and the reasons for their sudden incursions into Egypt.

Appendix:

Diodorus Siculus Library of History Book III. Translated by C. H. Oldfather. Loeb Classical Library:

“It will be fitting, in connection with the regions we have mentioned, to discuss the account which history records of the Amazons who were in Libya in ancient times. For the majority of mankind believe that the only Amazons were those who are reported to have dwelt in the neighbourhood of the Thermodon river on the Pontus; but the truth is otherwise, since the Amazons of Libya were much earlier in point of time and accomplished notable deeds. Now we are not unaware that to many who read this account the history of this people will appear to be a thing unheard of and entirely strange; for since the race of these Amazons disappeared entirely many generations before the Trojan War, whereas the women about the Thermodon river were in their full vigour a little before that time, it is not without reason that the latter people, who were also better known, should have inherited the fame of the earlier, who are entirely unknown to most men because of the lapse of time. For our part, however, since we find that many early poets and historians, and not a few of the latter ones as well, have made mention of them, we shall endeavour to recount their deeds in summary, following the account of Dionysus who composed a narrative about the Argonauts and Dionysus, and also about many other things which took place in the most ancient times.

Now there have been in Libya a number of races of women who were warlike and greatly admired for their manly vigour; for instance, tradition tells us of the race of Gorgons, against whom, as the account is given, Perseus made war, a race distinguished for its valour; for the fact that it was the son of Zeus (i.e. Perseus), the mightiest Greek of his day, who accomplished the campaign against these women, and that this was his greatest Labour may be taken as proof of both the pre-eminence and the power of the women we have mentioned. Furthermore, the manly prowess of those of whom we are now about to write presupposes an amazing pre-eminence when compared with the nature of the women of our day.

We are told, namely, that there was once in the western parts of Libya, on the bounds of the inhabited world, a race which was ruled by women and followed a manner of life unlike that which prevails among us. For it was the custom among them that the women should practise the arts of war and be required to serve in the army for a fixed period, during which time they maintained their virginity; then when the years of their service in the field expired, they went in to the men for the procreation of children, but they kept in their hands the administration of the magistracies and all the affairs of state. The men however, like our married women, spent their days about the house, carrying out the orders which were given them by their wives; and they took no part in military campaigns or in office or in the exercise of free citizenship in the affairs of the community by virtue of which they might become presumptuous and rise up against the women. When their children were born the babies were turned over to the men, who brought them up on milk and such cooked foods as were appropriate to the age of the infants; and if it happened that a girl was born, its breast were seared that they might not develop at the time of maturity; for they thought that the breasts, as they stood out from the body, were no small hindrance in warfare; and in fact it is because they have been deprived of their breasts that they are called by the Greeks Amazons (a -maston/ without a breast).

As mythology relates, their home was on an island, because it was in the west, was called Hespera, and it lay in the marsh Tritonis. This marsh was near the ocean which surrounds the earth and received its name from a certain river Triton which emptied into it; and this marsh was also near Ethiopia and that mountain by the shore of the ocean which is the highest of these in the vicinity and impinges on the ocean and is called by the Greeks Atlas. The island mentioned above was of great size and full of fruit bearing trees of every kind, from which the natives secured their food. It contained also a multitude of flocks and herds, namely of goats and of sheep, from which the possessors received milk and meat for their sustenance; but grain the nation used not at all because the use of this fruit of the earth had not yet been discovered amongst them.

The Amazons, the account continues, being a race superior in valour and eager for war, first of all subdued all the cities on the island except the one called Mene, which was considered to be sacred and was inhabited by Ethiopian Ichthyophagi (fish eaters), and was also subject to great eruptions of fire and possessed a multitude of precious stones which the Greeks call anthrax, sardion, and smaragdos; and after this they subdued many of the neighbouring Libyans and the nomad tribes, and founded within the marsh Tritonis a great city which they named Cherronesus (Peninsula) after its shape.

Setting out from the city of Cherronesus, the account continues, the Amazons embarked upon great ventures, a longing having come over them to invade many parts of the inhabited world. The first people against whom they advanced, according to the tale, was the Atlantians, the most civilised men among the inhabitants of these regions, who dwelt in a prosperous country and possessed great cities; it was amongst them we are told, the mythology places the birth of the gods, in the regions which lie along the shore of the ocean, in this respect agreeing with those among the Greeks who relate legends, and about this we shall speak in detail later.

Now the queen of the Amazons, Myrina, collected, it is said an army of thirty-thousand foot soldiers and three thousand cavalry, since they favoured to an unusual degree the use of cavalry in their wars.

For protective devices they used the skins of large snakes, since Libya contains such animals of incredible size, and for offensive weapons, swords and lances; they also used bows and arrows, with which they struck not only when facing the enemy but also when in flight, by shooting backwards at their pursuers with good effect. Uponentering the land of the Atlantians they defeated in a pitched battle the inhabitants of the city of Cerne, as it is called, and making their way inside the walls along with the fleeing enemy, they got the city into their hands; and desiring to strike terror into the neighbouring peoples they treated the captives savagely, put to the sword the men from youth upward, led into slavery the children and women, and razed the city. But when the terrible fate of the inhabitants of Cerne became known among their fellow tribesmen, it is related that the Atlantians, struck with terror, surrendered their cities on terms of capitulation and announced that they would do whatever should be commanded them, and that the queen Myrina, bearing herself honourably towards the Atlantians, both established friendship with them and founded a city to bear her name in place of the city which had been razed; and in it she settled both the captives and by any native who so desired. Whereupon the Atlantians presented her with magnificent presents and by public decree voted her notable honours, and she in return accepted their courtesy and in addition promised that she would show kindness to their nation. And since the natives were often being wared upon by the Gorgons, as they were named, a folk who resided upon their borders, and in general had the people lying in wait to injure them, Myrina, they say, was asked by the Atlantians to invade the land of the aforementioned Gorgons. But when the Gorgons drew up their forces to resist them a mighty battle took place in which the Amazons, gaining the upper hand, slew great numbers of their opponents and took no fewer than three thousand prisoners; and since the rest had fled for refuge into a certain wooded region, Myrina undertook to set fire to the timber, being eager to destroy the race utterly, but when she found that she was unable to succeed in her attempt she retired to the borders of her country.

Now as the Amazons, they go on to say, relaxed their watch during the night because of their success, the captive women, falling upon them and drawing the swords of those who thought they were conquerors, slew many of them; in the end, however, the multitude poured in about them from every side and the prisoners fighting bravely were butchered one and all. Myrina accorded a funeral to her fallen comrades on three pyres and raised up great heaps of earth as tombs which are called to this day ‘Amazon Mounds.’ But the Gorgons, grown strong again in later days, were subdued a second time by Perseus, the son of Zeus, when Medusa was queen over them; and in the end both they and the race of the Amazons were entirely destroyed by Heracles, when he visited the regions to the west and set up his pillars in Libya, since he felt that it would ill accord with his resolve to be the benefactor of the whole race of mankind if he should suffer any nations to be under the rule of women. The story is also told that the marsh Tritonis disappeared from sight in the course of an earthquake, when these parts of it which lay towards the ocean were torn asunder.

As for Myrina, the account continues: She visited the larger part of Libya, and passing over into Egypt she struck a treaty of friendship with Horus, the son of Isis, who was king of Egypt at that time, and then after making war to the end upon the Arabians and slaying many of them, she subdued Syria; but when the Cilicians came out with presents to meet her and agreed to obey her commands, she let those free who yielded to her of their free will and for this reason they are called to this day the ‘Free Cilicians’. She also conquered in war the races in the region of the Taurus, peoples of outstanding courage, and descended through Greater Phrygia to the sea (i.e. the Mediterranean); then she won over the land lying along the coast and fixed the bounds of her campaign at the Caicus River. And selecting in the territory which she won by arms sites well suited for the founding of cities, she built a considerable number of them and founded one (i.e. the city of Myrina in Mysia: cp. Strabo 13.3.6.) which bore her own name, but the others she named after the women who held the most important commands, such as Cyme, Pitana, and Priene.

These, then, are the cities she settled along the sea, but others, and a larger number; she planted in the regions stretching towards the interior. She seized also some of the islands, and Lesbos in particular, on which she founded the city of Mitylene, which was named after her sister who took part in the campaign. After that, while subduing some of the rest of the islands, she was caught in a storm, and after she had offered up prayers for her safety to the Mother of the Gods (i.e. Cybele), she was carried to one of the uninhabited islands; this island, in obedience to a vision which she beheld in her dreams, she made sacred to the goddess, and set up altars there and offered magnificent sacrifices. She also gave it the name of Samothrace, which means when translated into Greek, ‘sacred island’, although some historians say that it was formerly called Samos and was then given the name of Samothrace by Thracians who at one time dwelt on it.

However, after the Amazons had returned to the continent, the myth relates, the Mother of Gods, well pleased with the island, settled in certain other people, and also her own sons, who were known by the name of Corybantes- who their father was is handed down in their rites as a matter not to be divulged; and she established the mysteries which are now celebrated on the island and ordained by law that the sacred area should contain the right of sanctuary.

In these times, they go on to say, that Mopsus the king of the Thracians, invaded the land of the Amazons with an army composed of fellow exiles, and with Mopsus on the campaign was also Sipylus the Scythian, who had likewise been exiled from that part of Scythia which borders on Thrace. There was a pitched battle, Sipylus and Mopsus gained the upper hand, and Myrina, the queen of the Amazons and the larger part of the rest of her army were slain. In the course of years, as the Thracians continued to be victorious in their battles, the surviving Amazons finally withdrew again into Libya.

And such was the end, as the myth relates, of the campaign which the Amazons of Libya made.”

Sources cited:

Diodorus Siculus, Library of History

Pliny, Natural History

Peter James, The Sunken Kingdom

Strabo, Geography

Ovid, Metamorphoses

Herodotus, Histories

Quintus Smyrnaeus, The Fall ofTroy

Michael Wood, In Search of the Trojan War

George Bean, Aegean Turkey

George Bean, Lycian Turkey

George Bean, Turkey beyond the Maeander

Nonnus, Dionysiaca

Georges E. Vougioukalakis et al. 2019, Volcanism of the South Aegean Volcanic Arc

The Rough Guide to Turkey

Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War

Pausanias, Guide to Greece

R.H.C.Davis, The Medieval Warhorse, 1989

Edward Bacon, Archaeology Discoveries in the 1960s

M. N. van Loon, Anatolia in the Second Millennium

T.H. Carpenter, Art and Myth in Ancient Greece

Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound

Stasinus of Cyprus or Hegesias of Aegina, Cypria Fragment 21