Who was Tantalus? Part One: Tantalis or Atlantis? © Nicholas Costa 2026

Pliny states: “In the same region there was [once] Tantalis, the capital of Maeonia, where Magnesia [ad Sipylum] now stands.” (Natural History 5. 31) Elsewhere Pliny discusses geological changes and mentions that Tantalis was destroyed by a catastrophe. He notes that where the city once stood, a lake (Lake Sale) formed after an earthquake “swallowed” the city, a detail supported by other ancient authors like Pausanias and Strabo. He uses this reference to explain that the “modern” city of Magnesia was built upon or near the ruins of this legendary capital, physically linking the mythological age of Tantalus to the historical Roman province of Asia.

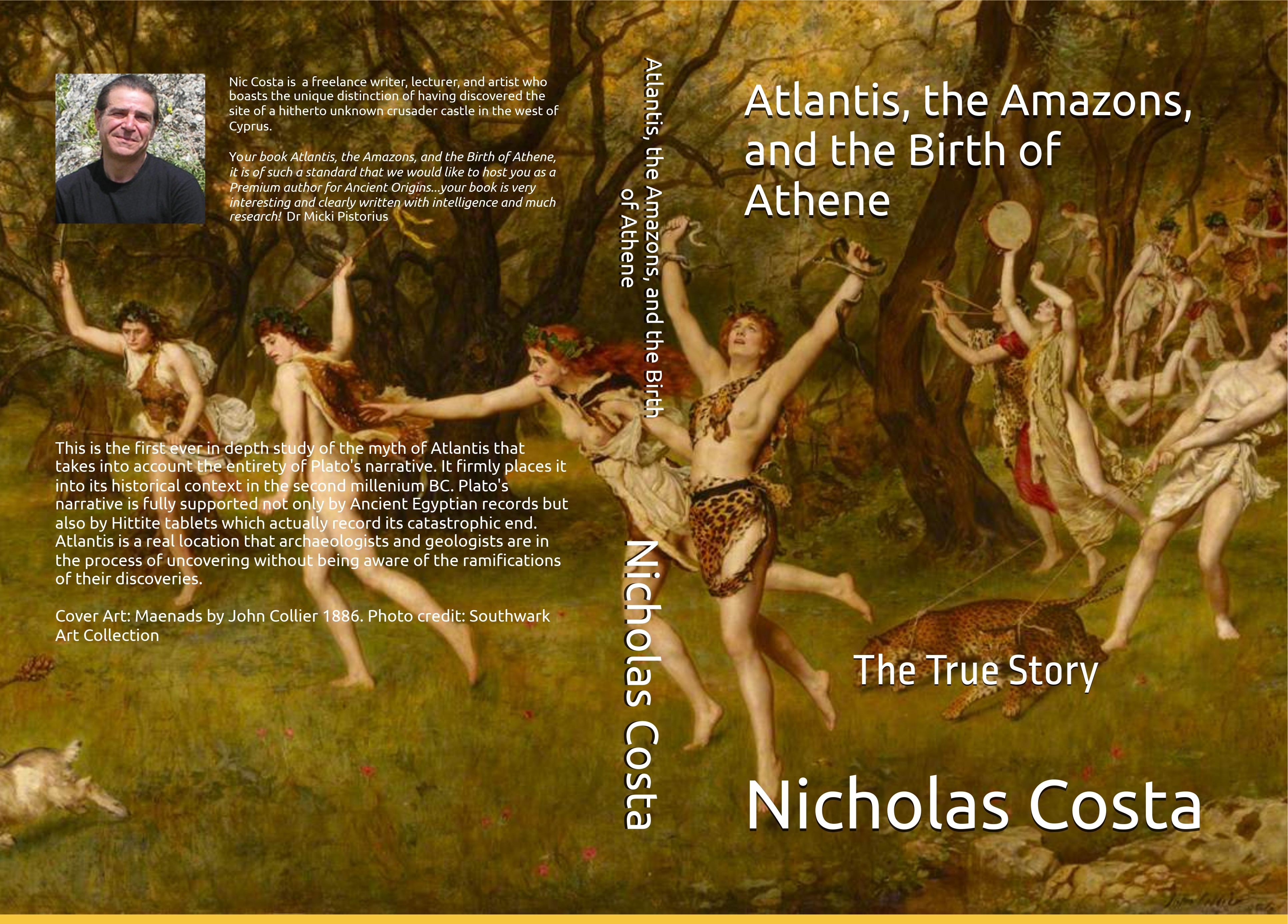

Peter James

Peter James in his book The Sunken Kingdom, the Atlantis Mystery Solved, 1995 identified this precise location as the source for the myth of Atlantis. James has since stated in an email to the author that he never claimed to have found a solution he wrote:

“Please note that I do not think that Atlantis was in Turkiye!!! People have been mislead by something the publishers added to the book jacket. My method was literary criticism and to investigate the sources that Plato used for his philosophical construct. I identified the core story, the legend behind his story, as Tantalis near Manisa. If you cite my book in your writing I would appreciate it if you could make this clear. (Email to author Sept 23 2023)

Most commonly the ancient city of Tantalis (ancient Magnesia ad Sipylum) was identified in antiquity as being located at the foot of Mount Sypilius at or near what is now Manisa in Turkey. It is situated approximately 32-40 km (20 to 25 miles) northeast of the coastal city of Izmir. (Manisa/Tantalis is situated in the Gediz River valley.

However there was another location some 33 km (21 miles) distant which was also remembered as the original site of Tantalis. This was a small peninsula located in what is now the Tepekule neighborhood in the Bayrakl? district of Izmir. In antiquity it would have jutted out into the Aegean sea. It was here that ancient Izmir (Smyrna) was built on the small peninsula covering an area of approximately ten hectares (24.71 acres). It was located on the northeast of the ?zmir gulf. The mound ultimately became landlocked due to the silt deposited by floods from the Meles River (Meles Çay?) and now sits in the Bornova plain. According to recent excavations the earliest settlement of Tepekule dates back to the Bronze Age.

Recent research has uncovered evidence that an earthquake and tsunami really did occur in Northwest Anatolia around 1300 BC, approximately the same time period as that allocated by the ancient chronographers to the Tantalus myths.

For example Duran and Sozbilir in a paper entitled “Seismic Activity of the Manisa Fault Zone in Western Turkey” identified a significant surface-rupturing earthquake which they estimate to have occurred sometime between 1500 BC to 600 BC. This is further focused by archaeological evidence at Troy VIh dated to c1300 BC which reveals a destruction layer caused by a massive earthquake. In a paper entitled Revision of the tsunami catalogue affecting Turkish coasts and surrounding regions. Y. Altino et al, 2011 formally lists the c. 1300 BC event as a verified prehistoric tsunami triggered by the earthquake that struck Northwest Anatolia.

Tantalis or Tantalus

Given that the name Tantalis was applied to two entirely different locations it should be evident that it was a name that actualy was once applied to the whole region since it had suffered a major catastrophe and therefore became remembered coloquialy as Tantalis, the kingdom of the Tantalids, the first legendary dynasty of Lydia. Strabo notes that Tantalus’s wealth came from the mines of both Phrygia and Lydia (Mount Sipylus) suggesting that “Tantalis” was in fact the nickname of a much larger industrial and territorial empire (Geography 14.5.28). Indeed Stephanus of Byzantium, in his Ethnica explicitly defines Tantalis as “a city and country (chora)” named after Tantalus. The name actually translates as “of or belonging to Tantalus.”

The Tantalis narratives as evidenced by the names are in fact metaphors for what happened to the region as a consequence of the airburst of c1327 BC which was recorded in the Hittite tablets. As noted Tantalis is a direct grammatical derivative of Tantalus. Tantalus was depicted as the ruler of Lydia and variously Phrygia (Strabo, Geography.12. 8.1.) The name Tantalus in fact represents a reduplication of the root of the Greek word talas “wretched” or “suffering.” Thus in this context Tantalis is none other than the wretched or devastated land

Ancient Wordplay

The Greeks reveled in wordplay. They demonstrably enjoyed playing with names—including rearranging letters (anagrams) or slightly altering sounds (paronomasia). It was a well-established practice in antiquity.

1. Ancient or Onomastic Wordplay Techniques:

Paronomasia: This is the juxtaposition of similar-sounding words to suggest a deeper connection or to create humor.

Anagrams (Transposition): While modern-style crossword anagrams were less common, the practice of rearranging letters to find “hidden meanings” in names dates back at least to the 3rd century BCE with the poet Lycophron.

Metathesis: In linguistics, this is the actual switching of sounds within a word (e.g., cast vs cats), which occurred both naturally in dialects and intentionally in literary puns.

2. Plato’s paidea or “Etymology Games”

Plato himself was a famous practitioner of this. In his dialogue Cratylus, he spent considerable time arguing that names are not arbitrary but reflect the “nature” of the things they describe. He often “stretched” or “rearranged” words to prove these links.

Onomastic wordplay, playing with names to reveal hidden meanings was a hallmark of ancient Greek literary and philosophical culture. So whilst Atlantis and Tantalis aren’t perfect letter-for-letter matches in the original Greek, the act of manipulating names to find deeper truths was extremely common:

1. The Concept of Nomen Omen

The Greeks believed in the principle of nomen omen—the idea that a name is a “sign” or “omen” that reveals an individual’s destiny. For instance Pythagoras (6th century BC) is often credited with using anagram-like techniques to uncover philosophical truths hidden in words. Whilst Alexander the Great famously acted on an anagram during the siege of Tyre. After dreaming of a satyr (satyros), his seer pointed out that the letters could be rearranged to say “Tyre is yours” (Sa Tyros).

2. Plato’s Cratylus and Etymological Games

Plato, who introduced the Atlantis story, wrote an entire dialogue called the Cratyluswhich was dedicated to the “correctness of names.” In it, he (through Socrates) engages in what is now known as “creative etymology”—stripping, adding, or rearranging sounds in names to explain their essence. Plato argues that names aren’t just arbitrary labels but “instruments” for teaching. He frequently links names that sound similar (like Tantalus and Talantos, “the sufferer”) to prove a point about a person’s character:

“The name of Tantalus is also given with the greatest propriety, if the legends about him are true. He seems to have been called Tantalus because he was talantatos (the most wretched or who has to bear much), if you derive the name from talas (wretched); and the story of the stone which hangs over his head is in marvelous agreement with his name; for he seems to be one who wavers (talanteuomenos) and is always in a state of suspense.” (Cratylus, 395e)

3. Professional “Anagrammatists”

By the 3rd century BC, poets like Lycophron made a profession out of creating complex anagrams for royalty. For instance he famously rearranged the name of King Ptolemy Ptolemaios to mean “Of Honey” Apo melitos, (Tzetzes, Scholia to Lycophron).

Why Atlantis and Tantalis fit this tradition:

Even though they aren’t perfect anagrams in the strict technical sense, the phonetic similarity (-t-a-n-t-a-l-) would have been highly significant to an ancient audience. For a philosopher like Plato, presenting a story about “Atlantis” (ostensibly named for a giant who bears the world) that sounds remarkably like “Tantalis” (named for a king whose hubris led to eternal suffering) would be a deliberate and powerful piece of thematic wordplay.

Next: Part Two: Who was Tantalus?

Leave a Reply