Who was Pelops By Nicholas Costa © 2026

Has anybody ever wondered how strange it is that when Pelops traveled from Anatolia his landing place was at Pisa on the north west of the Peloponnese rather than somewhere on the east coast of the Greek mainland? This underlines the fact that Pelops was never a human being.

One key element of the Tantalus narrative is his son Pelops. According to Clement of Alexandria the Palladium which fell from the sky in Anatolia

‘‘ was made out of the bones of Pelops…” (Protreptikos, 4.47.6).

Euripides stated that “Tantalus, the blest… now he hovers in the air, fearing the rock which hangs over his head… he gave life to Pelops…” (Euripides, Orestes 4–11).

Thus Pelops himself is a metaphor for a fragmenting bolide rather than a real person.

The myth of Pelops divides into two distinct parts, as follows: c1327 BC

- The Initial Airburst:

The myth states that Tantalus wanted to make an offering to the Gods so he cut his son Pelops into pieces and made his flesh into a stew which he then served to them. All but one refused to eat it. For his crime Tantalus was banished to Tartarus (killed). Demeter, who signified the Earth, was the deity remembered as mistakenly eating his shoulder bone which significantly was the part that was depicted as falling to earth.

Memories of the Subsequent Eruption at Yiali:

Pelops was depicted as being succeeded upon the throne of Lydia by Agron ( the wilderness). The abreviated nature of the extant Excerpta Latina Barbari chronology has evidently combined two separate listings. It has been commonly assumed that the Agron that suceeded Tantalus was the same as the one listed by Herodotus as a son of Ninus a long time later c1192 BC. This was not the case. Mythology knows of another Agron, one who fits the chronological picture very well. He was depicted as living on the island of Cos with his father the arrogant Eumelus son of Merops ruler of Cos. They were all notably punished for their impiety. Artemis killed Merops’ wife with arrows, whilst Merops, Eumelus and his children were turned into birds. (Antoninus Liberalis, Metamorphoses § 15). A suitable metaphor for what was left of Yiali volcano post eruption, birds flying above a wasteland.

Notably the name Eumelus also appears in Plato’s Atlantis narrative as the younger twin brother of Atlas. Plato wrote:

“To his twin brother, who was born after him, and obtained as his lot the extremity of the island towards the Pillars of Heracles, facing the country which is now called the region of Gades in that part of the world, he gave the name which in the Hellenic language is Eumelus, in the language of the country which is named after him, Gadeirus” (Critias 114a–114b)

The name Eumelus (“rich in sheep”) evidently acted as a metaphor for the location prior to the eruption

2. An Airburst/ Impacting Bolide at Olympia c1323 BC:

In the second part of the story Pelops was ritually reassembled and brought back to life, his shoulder replaced with one of ivory made for him by Hephaestus. After Pelops’ resurrection, Poseidon took him to Olympus, and gave him a divine golden chariot. It was by means of this chariot that Pelops managed to fly across the sea and arrive at Pisa in the northwestern Peloponnese which was subsequently renamed after him. When Zeus found out that Tantalus had revealed secrets of the gods he angrily threw his son Pelops out of Olympus.

Any Early Understanding of the Periodic Nature of Comets?

According Pindar (Olympian Ode 1), who rejected the concept of the a “cannibal banquet”—in which Tantalus served his son Pelops as a meal to the gods. Tantalus’s real offense was revealing divine secrets to his mortal friends, and because of this Zeus punished him. Tantalus was condemned to his eternal torment under a celestial hanging rock for his betrayal. Pelops, who had been living on Olympus as the favorite of Poseidon, was subsequently thrown out of Olympus. This myth implies that there was an awareness of the periodic nature of comets in Anatolia as early as the 14th century BC (hence the metaphor of stealing the secrets of the gods). Likewise the figure of Atlas (who is a metaphor for western Anatolia) is remembered as one who:

“had perfected the science of astrology and was the first to publish to mankind the doctrine of the sphere; and it was for this reason that the idea was conceived that he was actually carrying the entire heavens upon his shoulders.” (Diodorus, Bibliotheca Historica 3.60.2)

Pelops’ name

Interestingly (given that my analysis focuses upon Anatolia as the fountainhead of Plato’s Atlantis narrative) that Plato in his Cratylus (399 BC) text focused explicitly upon the names and cited philosophical etymologies of the three key ‘human’ figures associated with the catastrophe in Anatolia: Pelops, Niobe, and Tantalus. Had he begun researching the subject at this point in time? He was to write his Atlantis narratives the Timaeus and Critias c.360-50 BC. Was this merely coincidental?

According to Plato (Cratylus 395c-d), the name Pelops is derived from pelas meaning “near” and ops meaning “face” which he then turns into a philosophical metaphor.

In the Scholia on Pindar’s Olympian 1 one can find statements linking the name to pelos and ops, thus mud face/ eye or to the words for pelios dark and face/eye.

All the interpretations are appropriate since Pelops represents a near earth airburst / impacting meteorite. In the first manifestation he acts as the metaphor for the airburst of c1327 BC. In the second manifestation he acts as a metaphor for a meteorite which exploded or impacted near Pisa in the north west Peloponnese.

This is reinforced by the allusions to him being resurrected and riding a golden chariot across the Aegean to get to his destination at Pisa.

Pindar states that: “[Poseidon] gave him a golden chariot and horses with wings that never tire.” (Olympian Odes 1.86–87).

This is confirmed by Pseudo-Apollodorus, Epitome 2.3 who states “[Pelops] had received a chariot from Poseidon which could run even over the sea.”

Bolide Impact/ Earthquake in Southern Euboea c1323 BC

Buried within the narrative is memory of other lesser impact events. In the story relating to Myrtilus (Hyginus, Fabulae 8; Pausanias, Description of Greece 8.14.10–11) Myrtilus is depicted as being thrown from the Pelops chariot and falling into the sea near Cape Geraestus (Geraistos) on the island of Euboea. Whilst Tityus was ‘born’ just 15 kilometers (9 miles) away at Elarion near Carystus. These events significantly overlap pointing therefore to a real event involving the fragmentation of an incoming bolide. Likewise, Tityus is depicted as being killed at Panopeaia in Phocis where his grave was said to be located. It is some 120–130 kilometers (about 75–80 miles) northwest of Carystus.

The Four Year Gap: C1327- c1323 BC

That there was a gap between the events is recorded in the Excerpta Latina Barbari which states that “Pelops son of Tantalus, [reigned] 4 years [in Lydia/Phrygia]. Afterwards, having been expelled, he came to the western parts and settled in the Peloponnese.”

As stated Pelops himself was evidently a metaphor for the subsequent impacting bolide. According to the mythology this would have occurred some 4 years after the original airburst above Ephesus As noted the myths additionally indicate meteorite falls above southern Euboea and Phocis followed by an impact/ airburst in the region of Pisa.

Lycophron metaphorically refers to “such remains as the funeral fire spared to abide in Letrina… of the son of Tantalus”.(Lines 52–55)

Temple of Hades

The latter catastrophe evidently led to the establishment of Olympia as a major centre of worship, and ultimately to the founding of the Olympic Games at 4 year intervals as a memorial perhaps to the dead. Indeed there was a Temple of Hades (which was a rarity in antiquity) located at the site which was ritually opened only once a year. According to Pausanias

“The sacred enclosure of Hades and its temple—for the Eleans have these among their possessions—are opened once every year, but not even then is anyone permitted to enter except the priest. The Eleans are the only people we know of who worship Hades… They give the following reason. They say that, since men only go down to Hades once, the doors of his temple should also be opened but once.” (Description of Greece, 6. 25. 2.)

The reputed traditional founders of the Olympic Games act as an affirmative focus upon this period, for Zeus, Heracles, and Pelops since they are all directly linked to the airburst of c1327 BC. Underlying them all is the figure of Artemis.

The Bones of Pelops

Pausanias writes that the Greeks fetched a “bone of Pelops—a shoulder-blade” from Pisa to ensure the fall of Troy. It was lost in a shipwreck off Euboea and later recovered in a net by a fisherman named Damarmenos. By Pausanias’ time (2nd century AD), he notes the bone had “disappeared… greatly decayed through the salt water“.(5.13.4–6).

However, he also identified a specific site near the Temple of Artemis Kordax in Pisa: “Not far from the sanctuary is a small building containing a bronze chest, in which are kept the bones of Pelops”.(5.13.4–6). He also writes of The Pelopion at Olympia (5.13.1) which he describes as a “sacred enclosure consecrated to Pelops” within the Altis at Olympia, where the hero received annual sacrifices of a black ram. The Altis was the final destination of the Sacred Way.

Aeacus

Although never directly appearing in a myth alongside Tantalus, he evidently represents the aftermath of the c1327 BC airburst. He is depicted as helping to rebuild the walls of Troy alongside Apollo and Poseidon.

The Ancient glosses (found in the Etymologicum Magnum, the largest Byzantine lexicon c1150 AD and scholia) state: “Aeacus is named from aiazein which means ‘to wail’ or ‘to cry out aiai”

Aeacus is placed during the early construction of Troy. According to Pindar he assisted the gods Apollo and Poseidon in building the city’s walls (Olympian Ode 8). This is in the period immediately following the airburst.

James Frazer notes: ““Tradition ran that a prolonged drought had withered up the fruits of the earth all over Greece, and that Aeacus, as the son of the sky-god Zeus, was deemed the person most naturally fitted to obtain from his heavenly father the rain so urgently needed by the parched earth and the dying corn. So the Greeks sent envoys to him to request that he would intercede with Zeus to save the crops and the people. “Complying with their petition, Aeacus ascended the Hellenic mountain and stretching out pure hands to heaven he called on the common god, and prayed him to take pity on afflicted Greece. And even while he prayed a loud clap of thunder pealed, and all the surrounding sky was overcast, and furious and continuous showers of rain burst out and flooded the whole land…” (Clement of Alexandria, Strom. vi.3.28, p. 753)… According to Apollodorus, the cause of the dearth had been a crime of Pelops, who had treacherously murdered Stymphalus, king of Arcadia, and scattered the fragments of his mangled body abroad…. ”(Apollodorus, Library,3, footnotes by J. G. Frazer).

The Megadrought

The figure of Aeacus is seminal therefore in underling the truth behind the myths relating to the airbursts and their after effects in the region. Around 1300 BCE, the Eastern Mediterranean was entering a pivotal period of environmental transition that many scholars link to the Late Bronze Age collapse. Whilst earlier decades (c. 1450–1350 BC) were relatively moist, climate records from this era show a shift toward severe, multi-century instability characterized by the onset of the “3.2 ka BP event” which was the start of a 300-year drought. Below are some research papers relating to this.

Kaniewski et al. (2010): Published in Late second–early first millennium BC abrupt climate changes, this study uses pollen-derived proxies from Tell Tweini (Syria) to show the onset of drier conditions in the late 13th century BC.

Drake (2012): Published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, this review identifies a sharp decrease in Mediterranean Sea surface temperatures and rainfall specifically during the 13th and 11th centuries BCE.

Manning et al. (2023): This recent high-resolution study in Nature used tree rings from central Anatolia to pinpoint a three-year “extreme drought” (1198–1196 BCE) that coincides exactly with the collapse of the Hittite capital.

Finné et al. (2011): A comprehensive review in the Journal of Archaeological Science that synthesizes 6,000 years of Mediterranean climate, noting the 300-year dry period (3.2 ka BP) as a major turning point for Bronze Age societies.

Next: Olympia: Why was it so important? The true reason for the founding of the Olympic Games. c1323 BC

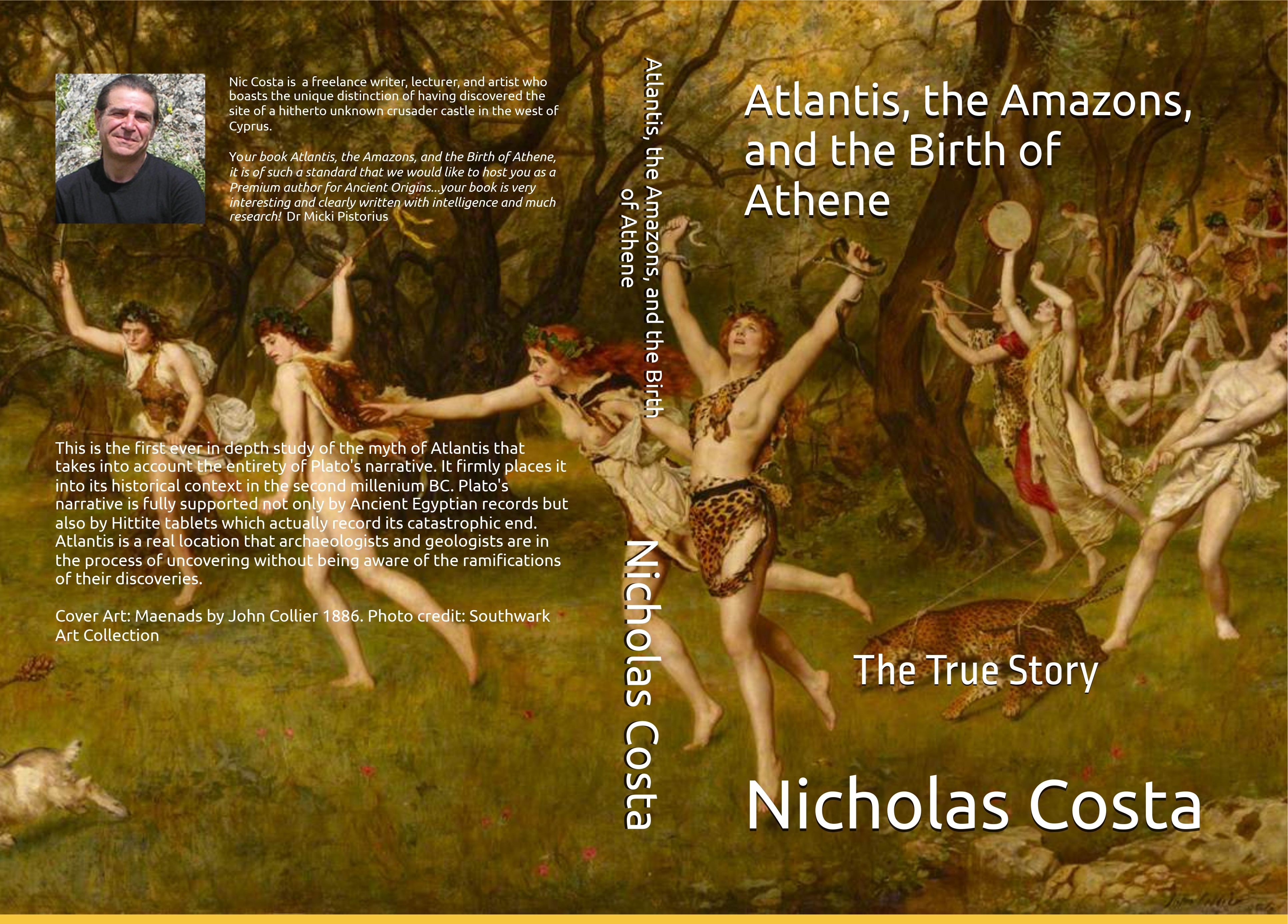

Now Available from Amazon:

Leave a Reply